Category: 游记Travel Records

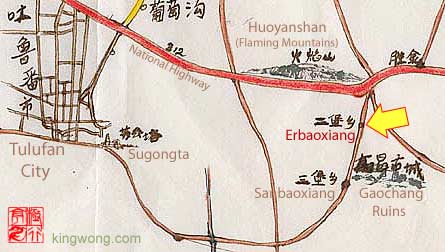

2006/05/28《二堡乡游记》Framing Erbaoxiang

The entrance area to the 高昌故城Gaochang Ruins, once the capital city of the

维吾尔Uygur ethnic people, was a popular hangout for the local kids. Little Uygur children would run around the ticket building touting their wares to the

incoming tourists, most were of the 汉族Han

ethnic group, coming here by the busload. A few kids remembered me from

yesterday came over to my side. The little boy who had convinced me to buy from him a ridulous pink and silver

hat came forward and gave me a small 馕nan,

a local bread made of wheat and maize. "Homemade." He proudly said as

I took a bite. I then took out my bag of raisins that I had brought earlier

at 苏公塔Sugong

Ta to share it with them. While we were eating by a shaded mud-brick

wall, I suddenly noticed a short little girl in a one-piece dark-red and

dotted dress standing silently observing from inside the ticket building.

Having been discovered, she came round to me on her violet rubber slippers;

on her waist was hung a ring of shiny bells.

The entrance area to the 高昌故城Gaochang Ruins, once the capital city of the

维吾尔Uygur ethnic people, was a popular hangout for the local kids. Little Uygur children would run around the ticket building touting their wares to the

incoming tourists, most were of the 汉族Han

ethnic group, coming here by the busload. A few kids remembered me from

yesterday came over to my side. The little boy who had convinced me to buy from him a ridulous pink and silver

hat came forward and gave me a small 馕nan,

a local bread made of wheat and maize. "Homemade." He proudly said as

I took a bite. I then took out my bag of raisins that I had brought earlier

at 苏公塔Sugong

Ta to share it with them. While we were eating by a shaded mud-brick

wall, I suddenly noticed a short little girl in a one-piece dark-red and

dotted dress standing silently observing from inside the ticket building.

Having been discovered, she came round to me on her violet rubber slippers;

on her waist was hung a ring of shiny bells.

"Very pretty, do you want one?"

Her sweet face glowed like an apricot as she pulled up the bells to eye level. She stood head to head with me while I was squatting and leaning my back on the wall; then she gently shook her bells as to put a spell on me. I fixed at the bells boringly, then turned my head as I finished my last bite of the bun.

"I don't need one."

"I give you one as a gift to remember. Here, take it."

She tactfully slided out the tiniest one and placed it on my hand. Then

I offered her my raisins. In an instant, her eyes dimmed as her round

face slowly widened, and those short lips curled inward a bit more; then,

by her cheeks a set of depressions suddenly formed as like two stones

suddenly found themselves sinking on quicksand. She casually picked up

one between her dirty little fingers, and bit it lightly with her teeth.

Then dropped it back on my hand. She repeated this twice more. Stopped.

And without further fuss, she swung her long black hair and walked away.

She tactfully slided out the tiniest one and placed it on my hand. Then

I offered her my raisins. In an instant, her eyes dimmed as her round

face slowly widened, and those short lips curled inward a bit more; then,

by her cheeks a set of depressions suddenly formed as like two stones

suddenly found themselves sinking on quicksand. She casually picked up

one between her dirty little fingers, and bit it lightly with her teeth.

Then dropped it back on my hand. She repeated this twice more. Stopped.

And without further fuss, she swung her long black hair and walked away.

I held up my peanut-size bell and shook it - a simple clash of cheap metals. In most cases it is a disposable - like all modern day disposables whose astronomical quantity is simply brutal. But I was delighted to receive the gift. Now this is surely a memory to sing about, I thought, as I carefully slided it through my key ring. Then I crossed the dirt road to the ticket building. Inside the ticket room several Han staffs were busy with paperworks. The man in charge there was curious about me and asked where I was from. A very common question. I would answer 四川Sichuan, 安徽Anhui, or 江苏Jiansu - poorer provinces that I know fairly enough to make a convincing lie. But I told the man 广东Guangdong, my home province. "From your accent, I knew you may be from the south. We have many Guangdong tourists coming here. But they all come in packs. Why are you here by yourself? Wouldn't it be boring?"

There were two other staffs, both woman, that were doing their work,

but now seemed attentive to our conversation. I probably looked odd enough

with my tripod, dirty rucksack and muddy clothings, unlike the packs coming

in with bright shirts and loose pants strapped with a black dressing belt

and carrying a pouched silver digital camera and an umbrella instead of

a tripod. So they wanted to hear me. "Well, I like to come and go whenever

I like. Another person would just be a burden, and I would find it hard

to work alone. If I feel bored and wanted to talk, I can always find someone.

I like strangers. Honest strangers always open up to other like-minded

strangers." I heard myself said. The women smiled. "Why don't you bring

your girlfriend along? She shouldn't be a problem." One of them said in

sisterly tone. My jaw dropped a little. I looked around the room: A long

counter steps down a little halfway as it divided a third of the room

- empty on the third, but fairly packed with several wood tables on the

remaining. Outside, the sounds of jingles were building up; then more

sounds. A group of tourists had just came in. The local suvenir vendors

by the doorway called out with the sounds of their products. "There is

this and there is that. I wanted both. But that is difficult. She would

not have come with me. The whole thing is just too long, too tiring, and

too demanding. Maybe too meaningless as well." I finally said. The women

looked a little puzzled, so I better get my ticket and leave. I handed

the 30 yuan to a woman for the ticket and left my tripod (which was not

allowed inside the ruins) with the man, who was secretly smiling. And

I walked out and waited on line to get in.

There were two other staffs, both woman, that were doing their work,

but now seemed attentive to our conversation. I probably looked odd enough

with my tripod, dirty rucksack and muddy clothings, unlike the packs coming

in with bright shirts and loose pants strapped with a black dressing belt

and carrying a pouched silver digital camera and an umbrella instead of

a tripod. So they wanted to hear me. "Well, I like to come and go whenever

I like. Another person would just be a burden, and I would find it hard

to work alone. If I feel bored and wanted to talk, I can always find someone.

I like strangers. Honest strangers always open up to other like-minded

strangers." I heard myself said. The women smiled. "Why don't you bring

your girlfriend along? She shouldn't be a problem." One of them said in

sisterly tone. My jaw dropped a little. I looked around the room: A long

counter steps down a little halfway as it divided a third of the room

- empty on the third, but fairly packed with several wood tables on the

remaining. Outside, the sounds of jingles were building up; then more

sounds. A group of tourists had just came in. The local suvenir vendors

by the doorway called out with the sounds of their products. "There is

this and there is that. I wanted both. But that is difficult. She would

not have come with me. The whole thing is just too long, too tiring, and

too demanding. Maybe too meaningless as well." I finally said. The women

looked a little puzzled, so I better get my ticket and leave. I handed

the 30 yuan to a woman for the ticket and left my tripod (which was not

allowed inside the ruins) with the man, who was secretly smiling. And

I walked out and waited on line to get in.

By now the area was crisscrossed with the new arrivals, and mixed with a steady stream of others coming out and getting onto their bus parked by the Gaochang wall. As I waited on line I caught a glance of the little bell girl moving slowly through the crowds. And from inside the crude wood doorway to the ruins, the shifting blinds of upright bodies and slant shadows had successively obliterated her; but as I faced the glaring desert sun, an afterglow of her doll-like body appeared like a mirage on the ochre landscape.

The

ancient city have mud walls (which were strenghened with straws inside)

that used to be 11 meters high and equally thick surrounding on four sides,

now less dramatic, but still impressive; a moat used to be outside. Inside

were all the mud-brick structures that, since the begining of the 明朝Ming

dynasty (1368-1644) when it had been abandoned after violent

wars with the Mongolians, had been transformed back into just lumps of

mud. 2 kilometers into this mud city lay the king's palace - an area all

tourists eventually dropped in by the cartload. Donkey carts were the

most convenient way to get there, and these were what everyone hopped

on for 20 yuan. But, of course, I walked the couple of kilometers there

under the blazing sun. Road signs were nonexistent, but directions were

obvious - I simply followed the donkey cart trails, all scorged deep into

the bare dusty roads. A few times I climbed higher to check out the landscape.

The

ancient city have mud walls (which were strenghened with straws inside)

that used to be 11 meters high and equally thick surrounding on four sides,

now less dramatic, but still impressive; a moat used to be outside. Inside

were all the mud-brick structures that, since the begining of the 明朝Ming

dynasty (1368-1644) when it had been abandoned after violent

wars with the Mongolians, had been transformed back into just lumps of

mud. 2 kilometers into this mud city lay the king's palace - an area all

tourists eventually dropped in by the cartload. Donkey carts were the

most convenient way to get there, and these were what everyone hopped

on for 20 yuan. But, of course, I walked the couple of kilometers there

under the blazing sun. Road signs were nonexistent, but directions were

obvious - I simply followed the donkey cart trails, all scorged deep into

the bare dusty roads. A few times I climbed higher to check out the landscape.

I

was careful to confirm my ground as a lot of these were originally houses

and I might foolishly dropped in and be the first visitor in 600 years.

What I saw is timeless: In one unbreaking mud-hue, two million square

meter area of naked polymorphic structures, collapsed houses, fallen stupas,

crumbled towers, and broken walls lay before the backdrop of the fiery

火焰山Huoyan

Shan (Flaming Mountains). Alien, I thought. But if civilizations

were to be ended by the surge of nuclear radiations, everything would

certainly have melted like this. Gouged through these mud matters were

what used to be the main roads, and today the donkey carts rumbled through

them just like the old days. I hiked off-road onto the jumbo of funny

shapes rising from the ground, much like a children's theme playground,

and was submerged below its sudden drops and depressions. In an hour I

came to the king's compound. The relative importance of this area is shown

by its isolation from the rest by means of more walls. And through a walled

path I entered into a square area. Beyond this empty square and up a few

steps was once a four-storied palace building. Immediately to the right

was an unusual adobe building: A truncated bald dome sat heavily atop

a low stocky square body; on its forehead was scribed a local message.

A smoothed path rolled up to its belly where a simple sharp arch died

an opening with its likeness. It is made entirely of mud - no nails, no

joints, just an ingenious method of stacking the mud-bricks together to

form the structure, including the truncated dome. This may been a recent

reconstruction of a temple.

I

was careful to confirm my ground as a lot of these were originally houses

and I might foolishly dropped in and be the first visitor in 600 years.

What I saw is timeless: In one unbreaking mud-hue, two million square

meter area of naked polymorphic structures, collapsed houses, fallen stupas,

crumbled towers, and broken walls lay before the backdrop of the fiery

火焰山Huoyan

Shan (Flaming Mountains). Alien, I thought. But if civilizations

were to be ended by the surge of nuclear radiations, everything would

certainly have melted like this. Gouged through these mud matters were

what used to be the main roads, and today the donkey carts rumbled through

them just like the old days. I hiked off-road onto the jumbo of funny

shapes rising from the ground, much like a children's theme playground,

and was submerged below its sudden drops and depressions. In an hour I

came to the king's compound. The relative importance of this area is shown

by its isolation from the rest by means of more walls. And through a walled

path I entered into a square area. Beyond this empty square and up a few

steps was once a four-storied palace building. Immediately to the right

was an unusual adobe building: A truncated bald dome sat heavily atop

a low stocky square body; on its forehead was scribed a local message.

A smoothed path rolled up to its belly where a simple sharp arch died

an opening with its likeness. It is made entirely of mud - no nails, no

joints, just an ingenious method of stacking the mud-bricks together to

form the structure, including the truncated dome. This may been a recent

reconstruction of a temple.  The

great Tang traveller monk and translator 玄奘Xuan

Zhuang1 was received here

by the Buddhist ruler. Since the second half of the 汉朝Han

dynasty (202 BCE - 220 AD), Buddhism had been vibrant in Central

Asia. Gaochang was then one of the main Buddhist centers on the northern丝绸之路Silk

Road. Xuan Zhuang preached here for about a month before he continued

his journey to India for Buddhist scriptures that he hoped will clarify

some contradictions. The king of 高昌国Gaochang

kingdom adored him so much that he refused to let him go. Xuan Zhuang

protested by refusing to eat and drink for three days til the king finally

gave in and assisted him with all neccessary people, horses, food and

documetations so he can pass Central Asia safely. Xuan Zhuang promised

the ruler that he will stay a year with him on his return. He never did.

On his return trip about severteen years later, he learned that the devout

king had passed away.

The

great Tang traveller monk and translator 玄奘Xuan

Zhuang1 was received here

by the Buddhist ruler. Since the second half of the 汉朝Han

dynasty (202 BCE - 220 AD), Buddhism had been vibrant in Central

Asia. Gaochang was then one of the main Buddhist centers on the northern丝绸之路Silk

Road. Xuan Zhuang preached here for about a month before he continued

his journey to India for Buddhist scriptures that he hoped will clarify

some contradictions. The king of 高昌国Gaochang

kingdom adored him so much that he refused to let him go. Xuan Zhuang

protested by refusing to eat and drink for three days til the king finally

gave in and assisted him with all neccessary people, horses, food and

documetations so he can pass Central Asia safely. Xuan Zhuang promised

the ruler that he will stay a year with him on his return. He never did.

On his return trip about severteen years later, he learned that the devout

king had passed away.

After a while I was alone here, and having nothing to do I squatted

on any shaded area. And squatting next to me was an Uygur guard, an 二堡乡Erbaoxiang

native in his first day on the job. He weared a gray uniform with a cap

and shoes, and looked not much older than twenty. Most of the time we

squatted there saying not a word. Every 15 minutes or so, we moved a little

toward the shade. There was not a chair here nor any permanent shade,

and access to any water and toilet was near the entrance, which he may

have to walk there if a donkey cart was not available. I pointed to a

high platform and the broken walls which he said were the remains of the

royal palace.  The

temple, he said, was reconstructed in 1980. Again we squatted in silence.

Soon trails of tourists with opened umbrellas streamed in following the

guides. They passed a wall where, suddenly, three local beauties appeared

in their fresh attires standing by the shade, waving and luring tourists

for memories together. They first entered the temple to cool off, which,

after 15 mins. of bumpy ride in the heat, was the only interior with a

roof to hide from the summer sun. Next they moved up to where we squatted

and introduced the towering walls. Then they left.

The

temple, he said, was reconstructed in 1980. Again we squatted in silence.

Soon trails of tourists with opened umbrellas streamed in following the

guides. They passed a wall where, suddenly, three local beauties appeared

in their fresh attires standing by the shade, waving and luring tourists

for memories together. They first entered the temple to cool off, which,

after 15 mins. of bumpy ride in the heat, was the only interior with a

roof to hide from the summer sun. Next they moved up to where we squatted

and introduced the towering walls. Then they left.

Silence and heat finally drove me away. I waved farewell to the guard and rushed back. On the way, I took a few more shots as the sun was now less harsh and structures became more defined. But my mind was set on to explore the town: While I was here late yesterday, too late to visit the ruins, I hopped on a taxi to get back to 吐鲁番Tulufan (Turfan or Turpan) city, about 46 kilometers away. As there were no convenient public buses to here, so the local method is to hire a taxi or a minivan. But the fare to the city is too high for anyone to afford, so the driver will seek out 4-5 other passengers, each pays 8-10 yuan. I got on a taxi at about 6pm. At first, the driver drove around casually looking for local passengers; but after half an hour with no signs of business, he became a little anxious. So he drove faster. A few times he stopped; he seemed to be recalling his lucky spots - then speed to it. Very soon an hour ticked away and still only the sight of me. Now the man became desperate. Meanwhile I sat in the back enjoying the free ride around the busy town. At this hour, most folks were outside welcoming the cool air. As I am a Han, the folks of this entirely Uygur town easily spotted me, and they naturally wondered. Still my luckless driver would not give up and made a few more hopeful rounds. Once a while he stopped to chat with a friend, but eventually he gave up the hunt. Instead he went from one brick house to another loading and unloading stuffs. And I just waited in the car cracking sunflower seeds. In another half an hour I met all his extended family members. When all the chores were done and nothing else seemed to itch anymore, he finally handed the car to another person who drove me through the desert and back to the city at night. In another half hour or so I was back in the city. As can be imagine, that was the best 10 yuan I had spent in Tulufan. Out of this ride I developed an intense interest in the town, so I planned to come back.

I went back to the ticket office to claim my tripod. The manager was surprised I took so long. "Have you eaten yet?" He asked, but without waiting for my answer he continued, "you must try a bowl of the local 凉面Liang Mian (Cool noodle)." After more than two hours circling in the heat, I was ready for food. So I asked where I can get it. Concerned of my ignorance and lack of experience, he asked one of the guides to take me to the spot. I thanked him generously; then happily followed the very pretty Han girl. Her hometown is in 敦煌Dunhuang, where the famous 莫高石窟Mogao Caves are located. Having been trained for years she now worked here as a guide for the government, and every month she would be transfer to a different location. She and her coworkers lived in Erbaoxiang for the during of their assignment. But in a few days she would be off to another location.

A short distance later, we came to a nearby area where a few youths were playing billiards. A vendor's cart was parked there with the noodles inside glass doors. As she had eaten so I ordered a bowl(2 yuan). Filling the bowl were short flat noodles, both white and yellow, mixed with a dark sauce. The sour smell of vinegar immediately smacked me awake. Along with vinegar was salt, and maybe a few grains of sugar and some soysauce. But I am poor at judging food. So as I gulped down the lot, she explained a few things about this local specialty.

"This is a special local food. You might feel that the saltiness intensifies thirst, but as you eat it you will feel a coolness in your throat. Eventually you will discover that it actually quench your thirst."

I don't know whether it quenched my thirst or not, but I felt much better. We walked back to the ticket building, and as we stood a little longer outside, she suddenly asked why I would spent so much time and energy travelling. I had been asked this many times but never found a satisfying answer. Maybe I travelled for the same purpose as 玄奘Xuan Zhuang. Or maybe for the same solitude as 李白Li Bai2. Or maybe for the same wanderlust as 徐霞客Xu Xiake3. Or maybe for the same carefreeness as 庄子Zhuangzi4. "I just wanted to get away." I said. As she was leaving to get back to work, I said we might meet again.

Now alone, I decided that I must leave to look around this 乡Xiang (township, a division used mainly in Xinjiang). As I was leaving the area, I felt someone tucked on my pants. It was the cute little bell girl.

"Shu shu (uncle) you owe me 4 yuan."

"Why?"

" The bell is 4 yuan."

"I thought you gave it to me as a gift."

"Nooooh, it is 4 yuan."

I unexpectantly found my hand digging into my pocket and pulled out the whole lot. My hand blindly sweeped across the metals and felt the round bell; then separated it. I handed it back to her.

"Here, I don't want it."

" I am not selling it to you."

"Well, I don't want it."

"I am not selling it to you."

I watched with amazement as she walked away. Her golden bells hung gasping below her waist as she entered the ticket building. I got to have a little daughter like her, I thought.

Now

that that was over, I walked away. Around a corner on a quiet street not

far from the ruins was a mosque. It has the usual strong mosaic patterns

covering the entire structure; the fascade has a high arched doorway below

the onion domed top; two large slender minarets guard each side. I set

up my tripod to take a shot of it. After a minute of moving around to

avoid the ugly overhanging electric wires and causing a black chicken

screaming from her favorite wall, I pack up. The mosque doesn't look very

interesting but I thought it maybe useful for other things, so I took

a shot. I continue down the dirt road, which is long and straight with

not a curve, as are all the others; flat-top brick houses line each side

and few trees are around to break the monotonous ochre look. In another

street, however, people became more abundant. Here, the locals would rather

not sit on chairs, but prefer to rest on platforms, which were often carpeted.

Now

that that was over, I walked away. Around a corner on a quiet street not

far from the ruins was a mosque. It has the usual strong mosaic patterns

covering the entire structure; the fascade has a high arched doorway below

the onion domed top; two large slender minarets guard each side. I set

up my tripod to take a shot of it. After a minute of moving around to

avoid the ugly overhanging electric wires and causing a black chicken

screaming from her favorite wall, I pack up. The mosque doesn't look very

interesting but I thought it maybe useful for other things, so I took

a shot. I continue down the dirt road, which is long and straight with

not a curve, as are all the others; flat-top brick houses line each side

and few trees are around to break the monotonous ochre look. In another

street, however, people became more abundant. Here, the locals would rather

not sit on chairs, but prefer to rest on platforms, which were often carpeted.

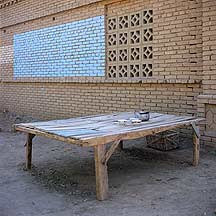

These

looked like low wood tables crudely nailed together, but some have metal

frames taken from beds, and instead of the soft mattresses, rough wood

planks replaced them. This furniture was ubiquous - as common as the door.

By now there was a good shadow on one side; on the other there was always

a tree or a makeshift tarp or roof. The folks sat there quietly without

a word, and almost always alone. They were mostly women and children.

The woman wore one-piece long dresses, or knee-length dresses with trousers,

and their heads were usually turpaned. The men were probably either still

at work or in mosques. Most Uygur today belongs to the Islamic faith.

Since the Tang dynasty, Islam had been slowly building up, starting from

southern Xinjiang. By the middle of 明朝Ming

(1368-1644), it became the dominant religion of Xinjiang.

These

looked like low wood tables crudely nailed together, but some have metal

frames taken from beds, and instead of the soft mattresses, rough wood

planks replaced them. This furniture was ubiquous - as common as the door.

By now there was a good shadow on one side; on the other there was always

a tree or a makeshift tarp or roof. The folks sat there quietly without

a word, and almost always alone. They were mostly women and children.

The woman wore one-piece long dresses, or knee-length dresses with trousers,

and their heads were usually turpaned. The men were probably either still

at work or in mosques. Most Uygur today belongs to the Islamic faith.

Since the Tang dynasty, Islam had been slowly building up, starting from

southern Xinjiang. By the middle of 明朝Ming

(1368-1644), it became the dominant religion of Xinjiang.

In

another turn I came to a quiet street again. But on this street the doors

looked a little unusual. They were painted with images. Flowers were the

most common subject, and these flowers spread out from vases and bloom

into almost patterns on rectangular spaces. The designs were painted with

solid colors - reds, browns, greens and yellows - on two-piece doorsdoors,

usualy painted with a red-brown color. I focused on a set of doors, and

as I shot it, the door suddenly opened. In a flash, the old woman quickly

closed it. I thought I ought to explain myself so I knocked. She openned

the door slowly again and in my best manner I asked if it was alright

that I take photos of her house. She did not understand much of what I

said, of course, because 普通话Putonghua

or 汉语Hanyu

(Han language, the national language of China) is not commonly spoken

here. But she nodded lightly and invited me in. As I stepped in I was

suddenly surprised by the bright even light. It flooded in from above,

through two rows of square brick columns the breadth and height of a man,

and on top each pair supports a skinless poplar log, seven in total, evenly

spaced from the front door to the backyard door; Running perpendicular

to these are much smaller logs, secondary branches crooked by nature,

that were cut just beyond the gaps and picked by another til the whole

lot filled the gaps enough for the next group of even finer branches that

completely weaved the remaining gaps lighttight. The brick colums stem

from two solid walls, of the same bricks, whose distance from one another

created the main space in between. In the back of this space is a narrow

second level, even with the base of the columns, with a wood staircase

that ran diagonally down the side of the right wall.

In

another turn I came to a quiet street again. But on this street the doors

looked a little unusual. They were painted with images. Flowers were the

most common subject, and these flowers spread out from vases and bloom

into almost patterns on rectangular spaces. The designs were painted with

solid colors - reds, browns, greens and yellows - on two-piece doorsdoors,

usualy painted with a red-brown color. I focused on a set of doors, and

as I shot it, the door suddenly opened. In a flash, the old woman quickly

closed it. I thought I ought to explain myself so I knocked. She openned

the door slowly again and in my best manner I asked if it was alright

that I take photos of her house. She did not understand much of what I

said, of course, because 普通话Putonghua

or 汉语Hanyu

(Han language, the national language of China) is not commonly spoken

here. But she nodded lightly and invited me in. As I stepped in I was

suddenly surprised by the bright even light. It flooded in from above,

through two rows of square brick columns the breadth and height of a man,

and on top each pair supports a skinless poplar log, seven in total, evenly

spaced from the front door to the backyard door; Running perpendicular

to these are much smaller logs, secondary branches crooked by nature,

that were cut just beyond the gaps and picked by another til the whole

lot filled the gaps enough for the next group of even finer branches that

completely weaved the remaining gaps lighttight. The brick colums stem

from two solid walls, of the same bricks, whose distance from one another

created the main space in between. In the back of this space is a narrow

second level, even with the base of the columns, with a wood staircase

that ran diagonally down the side of the right wall.

She

stood smiling quietly looking at me as I admired the construction. Then

as I was preparing the tripod to do my work, she stepped aside and sat

on a bed, made of a simple metal frame around a hard surface that was

covered with a carpet. The sitting surface was slightly higher than her

knees, so her rubber slippers tipped a little to stay on the ground. She

wore a white one-piece dress, loose like pajamas, with red speckles; and

on her head, covering her black hair, was a white headscarf. Behind the

bed was a room concealed by shadow. I slowly composed an image on the

old Hasselblad. Dead center on the glass I suddenly discovered a horizontal

florescent light, hanging parallel to the main logs. It had escaped me

totally. Like a clever insect it camouflaged itself among familiar environments

and shapes that we care less to look at. To the right was a tracter, then

further back was another tracter. I was having difficulty in containing

the whole room as I only have a normal lense. So I stepped back a little.

This caused my host to get up gracefully and disappeared in the room behind.

Another room was next to it.

She

stood smiling quietly looking at me as I admired the construction. Then

as I was preparing the tripod to do my work, she stepped aside and sat

on a bed, made of a simple metal frame around a hard surface that was

covered with a carpet. The sitting surface was slightly higher than her

knees, so her rubber slippers tipped a little to stay on the ground. She

wore a white one-piece dress, loose like pajamas, with red speckles; and

on her head, covering her black hair, was a white headscarf. Behind the

bed was a room concealed by shadow. I slowly composed an image on the

old Hasselblad. Dead center on the glass I suddenly discovered a horizontal

florescent light, hanging parallel to the main logs. It had escaped me

totally. Like a clever insect it camouflaged itself among familiar environments

and shapes that we care less to look at. To the right was a tracter, then

further back was another tracter. I was having difficulty in containing

the whole room as I only have a normal lense. So I stepped back a little.

This caused my host to get up gracefully and disappeared in the room behind.

Another room was next to it.  And

a couple more on the opposite wall. She came back soon with a bright red

pillow, which she placed gently on the bed before disappearing again.

But I had already stolen a few images of her. I hope she will forgive

me. After the shoot, I thought of going through the open backyard door

to check out the backyard, whose trees had drawn my interest. But that

seemed improper, so I thanked her and left.

And

a couple more on the opposite wall. She came back soon with a bright red

pillow, which she placed gently on the bed before disappearing again.

But I had already stolen a few images of her. I hope she will forgive

me. After the shoot, I thought of going through the open backyard door

to check out the backyard, whose trees had drawn my interest. But that

seemed improper, so I thanked her and left.

I

continued down the road, which was now heavily lined with low and wide

leafy trees. Under its velvet shadows, the local women sat quietly. More

than once I was surprised by their movements, as they turned to look at

me; Otherwise, hardly any person moved. Who would when the temperature

here averages 40°C (104°F) during the summer. There was reason that this

region was called 火州Huozhou

(literally, flaming or fire state) in the past. A few times a donkey cart

strolled passed, then a tracter rumbled by. Shadows now dominated the

scene, so that its primary colors were evenly mixed of ivory, green and

black. I strolled lightly through the area. I hardly take a photo, because

I found photography to be antropological in this condition, so I refrained

from shooting. I had my cameras stuffed in my backpack, and my tripod

was enclosed in a homemade slim and light fabric bag well-fitted to its

shape. When I did snap, however, it was swiftly done with my small Pentax

hanging on my belt. I don't like to be caught naked in the capture process.

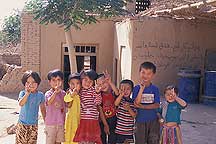

Unfortunately, I was soon discovered by the kids, who really called out

loudly. Suddenly, little kids hurried out from the shadows.

I

continued down the road, which was now heavily lined with low and wide

leafy trees. Under its velvet shadows, the local women sat quietly. More

than once I was surprised by their movements, as they turned to look at

me; Otherwise, hardly any person moved. Who would when the temperature

here averages 40°C (104°F) during the summer. There was reason that this

region was called 火州Huozhou

(literally, flaming or fire state) in the past. A few times a donkey cart

strolled passed, then a tracter rumbled by. Shadows now dominated the

scene, so that its primary colors were evenly mixed of ivory, green and

black. I strolled lightly through the area. I hardly take a photo, because

I found photography to be antropological in this condition, so I refrained

from shooting. I had my cameras stuffed in my backpack, and my tripod

was enclosed in a homemade slim and light fabric bag well-fitted to its

shape. When I did snap, however, it was swiftly done with my small Pentax

hanging on my belt. I don't like to be caught naked in the capture process.

Unfortunately, I was soon discovered by the kids, who really called out

loudly. Suddenly, little kids hurried out from the shadows.  Oh well. So I started snapping. Once they were beside me, they hopped

up and down to check out my Pentax, which I loaded with color film. I

handed the camera to them to play with, and they flipped and turned it,

puzzled for finding nothing. I was not surprised that they expected a

digital camera, because surely some proud owner would have had shown their

advance toys to some poor kids, and there are enough tourists in this

important tourist area to give that chance to a kid to wonder why. Although

disappointed they liked the attention, so all sorts of poses and gestures

were thrown to me. Then came along a teen. And I was immediately struck

by her looks, her clothings, her accessories, and especially her character.

So I went wild. I wanted a good image of her. And lucky for me the area

had enough interesting texture, so I was satisfied. After enough photos,

I waved goodbye and continued on my way. Still some of the kids followed

me, waving their hands. One by one they soon stopped. And I was alone

again.

Oh well. So I started snapping. Once they were beside me, they hopped

up and down to check out my Pentax, which I loaded with color film. I

handed the camera to them to play with, and they flipped and turned it,

puzzled for finding nothing. I was not surprised that they expected a

digital camera, because surely some proud owner would have had shown their

advance toys to some poor kids, and there are enough tourists in this

important tourist area to give that chance to a kid to wonder why. Although

disappointed they liked the attention, so all sorts of poses and gestures

were thrown to me. Then came along a teen. And I was immediately struck

by her looks, her clothings, her accessories, and especially her character.

So I went wild. I wanted a good image of her. And lucky for me the area

had enough interesting texture, so I was satisfied. After enough photos,

I waved goodbye and continued on my way. Still some of the kids followed

me, waving their hands. One by one they soon stopped. And I was alone

again.

I

continued down the road again, and soon I came to a little shop. I decided

to go in for an ice bar. Ice bars or ice-cream bars is one food that will

bubble over my head and became available within a very short time. Along

with tea-boiled chicken eggs and ice-tea drinks, these are ubiquous on

the road. The shop was empty. Immediately to the left wall of the doorway

were all the merchandises - soaps, toothpastes, towels, toilet papers,

shampoos, cups, crackers, preserved foods, soft drinks, brick teas, cheap

candies, crackers, sunflower seeds, rubber slippers, plastic toys - all

hung or stacked on shelves. On the ground lay boxes and boxes of beer.

And near the back wall was the ice-bar freezer covered with a cloth over

its lid. All these took up only about 2 steps of depth space on the side

wall. On the right were two rows of wood tables with accompanying benches

on each sides - a total of four sets. Right on top of one table near the

back wall were two fat blocks of white and yellow Liang Mian. These lay

on the aluminum trays like blocks of glossy cheeze.

I

continued down the road again, and soon I came to a little shop. I decided

to go in for an ice bar. Ice bars or ice-cream bars is one food that will

bubble over my head and became available within a very short time. Along

with tea-boiled chicken eggs and ice-tea drinks, these are ubiquous on

the road. The shop was empty. Immediately to the left wall of the doorway

were all the merchandises - soaps, toothpastes, towels, toilet papers,

shampoos, cups, crackers, preserved foods, soft drinks, brick teas, cheap

candies, crackers, sunflower seeds, rubber slippers, plastic toys - all

hung or stacked on shelves. On the ground lay boxes and boxes of beer.

And near the back wall was the ice-bar freezer covered with a cloth over

its lid. All these took up only about 2 steps of depth space on the side

wall. On the right were two rows of wood tables with accompanying benches

on each sides - a total of four sets. Right on top of one table near the

back wall were two fat blocks of white and yellow Liang Mian. These lay

on the aluminum trays like blocks of glossy cheeze.  I thought of the Han girl who introduced it to me. So I decided to eat

a bowl of liang mian instead getting the ice bar. But there was no one,

so I called out and waited for a respond. Soon, a woman peeked halfway

out of the curtained doorway in the rear wall. She was standing sideways

toward me, and in the grayness of the interior I made out the outline

of a slumbering infant on her arms. I pointed to the blocks of noodle

and said I would like a bowl. She nodded and disappeared into the interior.

I heard the voice of a man as I took a seat facing the food. She soon

came out. And slowly she unwrapped the plastic covers and began to slice

pieces from the block. Immediately flies swarmed to it. But she stayed

focus and continued her slicing. She was not particularly skillful at

it, as her slow and awkward cuts were not precise nor ordered in any particular

way. It did not seemed to be her job. Once she had enough cuts, she chopped

those into narrow strips. Then, she grapped some thick and texture pieces

from a few other bowls to add to the mix. Finally, she poured down the

sauce and handed the bowl to me.

I thought of the Han girl who introduced it to me. So I decided to eat

a bowl of liang mian instead getting the ice bar. But there was no one,

so I called out and waited for a respond. Soon, a woman peeked halfway

out of the curtained doorway in the rear wall. She was standing sideways

toward me, and in the grayness of the interior I made out the outline

of a slumbering infant on her arms. I pointed to the blocks of noodle

and said I would like a bowl. She nodded and disappeared into the interior.

I heard the voice of a man as I took a seat facing the food. She soon

came out. And slowly she unwrapped the plastic covers and began to slice

pieces from the block. Immediately flies swarmed to it. But she stayed

focus and continued her slicing. She was not particularly skillful at

it, as her slow and awkward cuts were not precise nor ordered in any particular

way. It did not seemed to be her job. Once she had enough cuts, she chopped

those into narrow strips. Then, she grapped some thick and texture pieces

from a few other bowls to add to the mix. Finally, she poured down the

sauce and handed the bowl to me.  It didn't look like the one I ate outside the ruins: it was much larger,

had much more variety in color, shapes and texture, and with a better

sauce. It really pays to be far from the tourist sites. I grapped a pair

of kuaizi and ate the lot slowly, I wanted to really taste it this time.

I will meet this food again elsewhere - in 哈密Hami,

平遥Pingyao,

榆林Yulin,

and 定边Dingbian

- and each was prepared differently. Before I finished the bowl, her husband

came out with their child; their other children soon joined in from inside.

Since the 1979 China implemented the 计划生育Planned

Birth policy to reduce population growth, but minorities, such

as the Uygurs, are exempted from this controversal program. This may explain

why the children here seemed more abundant than its number of adults.

In the villages of Anhui,

an eastern province, I would see adults walking around, one by one, holding

their single child.

It didn't look like the one I ate outside the ruins: it was much larger,

had much more variety in color, shapes and texture, and with a better

sauce. It really pays to be far from the tourist sites. I grapped a pair

of kuaizi and ate the lot slowly, I wanted to really taste it this time.

I will meet this food again elsewhere - in 哈密Hami,

平遥Pingyao,

榆林Yulin,

and 定边Dingbian

- and each was prepared differently. Before I finished the bowl, her husband

came out with their child; their other children soon joined in from inside.

Since the 1979 China implemented the 计划生育Planned

Birth policy to reduce population growth, but minorities, such

as the Uygurs, are exempted from this controversal program. This may explain

why the children here seemed more abundant than its number of adults.

In the villages of Anhui,

an eastern province, I would see adults walking around, one by one, holding

their single child.

Business in the shop was slow. Before leaving, I witnessed a couple

of kids coming in for some cheap sweets, and later a man picked up a few

beers. I paid, thanked her and left.  Again

I went down the road, made a turn or two and soon stopped by a main cross

road. Almost in the middle of the roads was a large hole dug into the

ground where an underground water tunnel passed; and a dozen or more of

little girls and boys jumped down into it, one by one. I wanted a few

images of this scene, so I employed my well-practiced routine: I turn

my back to it, take out my Pentax Me, set the approximate focus distance

and exposure compensation if needed; then turn around slowly toward the

scene with the camera still hidden in my back, and when the moment comes,

I reveal my camera, snap without looking into the viewfinder and immediately

hide it in my back again while I look away pretending not to care. Unfortunately,

too many eyes were watching; so after a few snaps I was caught again.

And like before, I was soon surrounded. So I snapped a few more, locked

the camera, and handed it to them to fool around with. They peeked through

the old camera as mud water were dripping from their bodies. I thought

of taking a peek at their little pool. The underground water canals are

part of an ancient irrigation system known as the karez. Besides the underground

channels there are also above-ground canals, vertical wells, and small

reservoirs that help contain and lead melted water from the nearby ice-capped

天山Tianshan Mountains to Tulufan.

Because of this ingenious irrigation system, its people and plants had

been able to survive in this desert 150 meters below sea-level, with some

of the hottest days on earth and not an inch of rain water all year round.

Again

I went down the road, made a turn or two and soon stopped by a main cross

road. Almost in the middle of the roads was a large hole dug into the

ground where an underground water tunnel passed; and a dozen or more of

little girls and boys jumped down into it, one by one. I wanted a few

images of this scene, so I employed my well-practiced routine: I turn

my back to it, take out my Pentax Me, set the approximate focus distance

and exposure compensation if needed; then turn around slowly toward the

scene with the camera still hidden in my back, and when the moment comes,

I reveal my camera, snap without looking into the viewfinder and immediately

hide it in my back again while I look away pretending not to care. Unfortunately,

too many eyes were watching; so after a few snaps I was caught again.

And like before, I was soon surrounded. So I snapped a few more, locked

the camera, and handed it to them to fool around with. They peeked through

the old camera as mud water were dripping from their bodies. I thought

of taking a peek at their little pool. The underground water canals are

part of an ancient irrigation system known as the karez. Besides the underground

channels there are also above-ground canals, vertical wells, and small

reservoirs that help contain and lead melted water from the nearby ice-capped

天山Tianshan Mountains to Tulufan.

Because of this ingenious irrigation system, its people and plants had

been able to survive in this desert 150 meters below sea-level, with some

of the hottest days on earth and not an inch of rain water all year round.

I had seen the above-ground canals and they were as muddy as the 黄河Huanghe

(Yellow River). So I didn't go to look at the water tunnel; instead

I continued down the road.  Some of the kids followed me, and one rode an adult's bike after me, screaming

and showing off his stunts on the way. Because of him, now more kids came

out to play. By now the sun was near setting, so I decided to load black

and white negative film because its ISO speed is twice higher than the

color Velvia 100 I was using. A few older girls came out as well, and

they wanted pictures with their little brothers and sisters. So my fingers

got quite busy. While all this was happening, the women just watched from

a distance. And when I picked up my camera, they disappeared into the

houses.

Some of the kids followed me, and one rode an adult's bike after me, screaming

and showing off his stunts on the way. Because of him, now more kids came

out to play. By now the sun was near setting, so I decided to load black

and white negative film because its ISO speed is twice higher than the

color Velvia 100 I was using. A few older girls came out as well, and

they wanted pictures with their little brothers and sisters. So my fingers

got quite busy. While all this was happening, the women just watched from

a distance. And when I picked up my camera, they disappeared into the

houses.  Some

just sat in the shadows. But one old woman invited me in. She wanted to

show me something, so I followed her to a large area where she lay them

out to sun-dry. They were mud-bricks. I wanted to know where the materials

came from and she led me to a concrete square container about a meter

square and half a meter high. There was nothing in there but this was

probably where mud, water and straws were mixed together. Near the wall

she proudly picked up a simple wood frame, and out of this mould came

these hundreds of mud-bricks that now lay neatly on the ground. From what

I had seen in this region, mud-bricks weren't used often anymore; their

primary use today is probably decorative, not structural, and for quick

and convenient construction. Most of the flat-top houses that I passed

were built of kiln-fired bricks and local poplar logs.

Some

just sat in the shadows. But one old woman invited me in. She wanted to

show me something, so I followed her to a large area where she lay them

out to sun-dry. They were mud-bricks. I wanted to know where the materials

came from and she led me to a concrete square container about a meter

square and half a meter high. There was nothing in there but this was

probably where mud, water and straws were mixed together. Near the wall

she proudly picked up a simple wood frame, and out of this mould came

these hundreds of mud-bricks that now lay neatly on the ground. From what

I had seen in this region, mud-bricks weren't used often anymore; their

primary use today is probably decorative, not structural, and for quick

and convenient construction. Most of the flat-top houses that I passed

were built of kiln-fired bricks and local poplar logs.

I was curious about how she prepared them, sell them, and for what price.

As well as how many she can produce in a month, and the construction method.

But she understood little Chinese and I not a word of the local language,

so I gave up.  While I was taking a few shots of the bricks, a teen came in and asked

if I could take a few pictures and mailed it back to her. She was determined

and she was pretty. And she was already dressed in her finest. So I said

ok. I set up my tripod and took out my Hasselblad. And I realized that

I have only a few frames of Velvia 100 left. I checked the ambient light

with my Minolta spotmeter. If I remember correctly, it was 1/4 second

at f/8 or, more likely, f/5.6 - too slow with not enough depth of field

for a group portrait. But I let things work their way. I focused on the

older girls and hope the best for the others.

While I was taking a few shots of the bricks, a teen came in and asked

if I could take a few pictures and mailed it back to her. She was determined

and she was pretty. And she was already dressed in her finest. So I said

ok. I set up my tripod and took out my Hasselblad. And I realized that

I have only a few frames of Velvia 100 left. I checked the ambient light

with my Minolta spotmeter. If I remember correctly, it was 1/4 second

at f/8 or, more likely, f/5.6 - too slow with not enough depth of field

for a group portrait. But I let things work their way. I focused on the

older girls and hope the best for the others.  I

took two frames. Later I would regret that I had not spent more time and

film on them. I asked her to write down the address, and she did her best

writing it in Chinese. But she wasn't satified, so she went out to get

it right.

I

took two frames. Later I would regret that I had not spent more time and

film on them. I asked her to write down the address, and she did her best

writing it in Chinese. But she wasn't satified, so she went out to get

it right.

Uygurs have their own language - a modified Turkic language that they inherited when Turk refugees settled in the area after the collapse of the Uygur empire in the Altai Mountains region. Long before this settlement,高昌Gaochang had been a Han garrison town since 西汉朝Western Han dynasty (206 BC - 8 BC). By year 439, there were a thousand Han households, along with a minority of other Central Asians, in this area. From then til its takeover by the Tang empire in 640 when it was made into a county, Gaochang went through four independent kingdoms, whose rulers were Hans. During the 安史之乱An Shi Rebellion (755 - 763), a Turkic tribe, the 回纥Huihe took advantage of the situation and took over the area. Later in the 8th century, when the Uygur empire in the Altai Mountains collapsed, some of its refugees settled in Gaochang and became the 高昌回纥Gaochang Huihe. When Genghis Klan swept through the area, they submitted to him. A part of the Islamic Mongols then settled in and its nobles ruled the area. Later in fourth year of 洪武Hongwu (1371), through a series of violent conflicts between the locals and the Mongol nobles, the Gaochang capital was lay to ruins and abandoned. But a large population of Mongolians still dwell in the area, mixing with the Huihe, as well as other Central Asias and Hans, and assimulated into the local culture. Their Islamic faith guadually dominated the region, replacing the millennium old Buddhism here. This mixture became the Uygur in the region today. They shared the modified Turkic language and the Islamic religion.

She came back with the address on a new sheet of paper. On it was written her father's name, Erbaoxing township, and its postal code. It was clearer but still written awkwardly, understandibly due to a lack of practice. I also asked for her name as well, and she wrote it beside the rest. In Tulufan city, my hotel proprietress, a Uygur, wrote the receipt in 拼音Pinyin5 rather than in Chinese characters. Perhaps because Pinyin is easier to remember and to write, and its linear direction is similar to the Uygur script which made it more adaptable than the multi-directional Chinese characters. I told her that she may have to wait more than 3 months for the pictures. She nodded. Half a year later, I sent the package to her. Inside were a selection of the pictures I took of the kids in the Gaochang Ruins, and the two groups of children I met while going through the township. And I wrote a few words asking her to distributed it to each kid in the photo. I sent it express and certified. I hope she got it.

I left the area and walked toward the main highway by the Flaming Mountains.

From there I should be able to find a car back to the city. By now the

shadows had taken over the roads and a small section of the highway glowed

in the far distant. As I walked I was hoping for a taxi to find me. I

listened for any horning sound. A distance later a car came and went right

passed me. It was a black car, not a taxi, but I waved hoping it might

go my way. A few houses away it stopped, then backed up slowly toward

me. Someone peeked out, "I thought it might be you." It was Francesco.

I met him in 乌鲁木齐WulumuqiWulumuqi

five days ago on a bus to 天池Tianchi

(Heavenly Pool). He and a friend were taking a long ride from

Italy toward east on their motorcycles. He invited me in and told me that

they had hired this car to check the sites in the area. Francesco was

in his twenties, rugged yet spoke gently, with amble patience - a quality

neccessary for long difficult travels. He spoke a little about the area,

but recommended a village in one of the valleys. Tulufan would be their

last stop in China. He asked me what my next move will be - an uncertainty

that hovered over my mind daily. I had not made up my mind yet. I would

like to stop by the grottoes at 敦煌Dunhuang

and the Pass at 嘉峪关市Jiayuguan

city. En

route I might have to stop at 哈密Hami

for buses to those locations. But I don't know. As I considered my options

a slight whisper came by the slit of a opened window; a strong wind gathered

speed and catching up behind us. Without warning the desert sand loomed

in the sky and enveloped the whole car. For a long moment we were trapped

in this cocoon of fiery sand, while a maroon glow, lighted by the dying

light of the sun, illuminated us. The car crawled like a larva, hesitating

often. I thought of my options again. I might have to chose one. ![]()

- 1.玄奘Xuan Zhuang (602 - 664). A traveller and Buddhist translater of the early 唐朝Tang dynasty (618 - 907). Having entered the monastery as a child, and had studied the scriptures for the past twenty years or so, he was frustrated by the apparent contradictions in the existent scriptures in China; and he believed that the only way to resolve them was through its original sources. So, about 11 years after the establishment of the empire, he head out of 西安Xian, its capital, toward India. He set out alone, determined to make the dangerous journey through unknown territories, deserts, snow mountains, hazardous passes, and roads guarded by murderous bandits. He returned 17 years later and was received by the Tang emperor, who asked him to recount his journey in writing. After satisfying the emperor with his 《大唐西域记》Records of the Western Regions, he retired to a monastery with a group of disciples and devoted the rest of his life to systematically translate the Sanskrit scriptures. Later in the 明朝Ming dynasty (1368-1644), The attributed author 吴承恩Wuchengen put together the existing folklores into the popular and mostly fictional novel 《西游记》Journey to the West that chronicles his journey, a feat so unbelievable that supernatural beings were invented to help explain how he survived the endless traps on the way. Among these supernatural beings are 孙悟空Monkey King, 猪八戒Lustful Pig, 沙僧Monk Sha, and 白龙马White Dragon Horse.

- 2.李白Li Bai (701 - 762). A poet of the 唐朝Tang dynasty (618 - 907). He travelled often, and his poetry reflects a supernatural union with nature, which he sought through solitude, travel and wine.

- 3.徐霞客Xu Xiake (1587 - 1641). A geographer and traveller of the 明朝Ming dynasty (1368-1644). He travelled throughout China, often by foot and through unknow and wild areas, on and off for 30 years. In his travels he noted the area's geography, geology, climate, food, people, customs,agruiculture, mining, arts and crafts, transportation and well-known sites. All these he collected and published posthumuously into 《游记》Youji (Travel Records), which total about 400,000 - 600,000 characters. A large amount for a single individual, however one counts it.

- 4.庄子Zhuangzi (about 369BCE - 286BCE). A writer and thinker of the 战国时代Warring States Era (475BCE - 221BCE) whose thoughts cannot be easily fit into any school of thought; otherwise, he would not be what he was. He was an anarchist if there is one. The influencial book, 《庄子》Zhuangzi is consider to be written by him, in whole or in parts.

- 5.汉语拼音Pinyin or Hanyu Pinyin (Chinese Phonetic System). It is a pronounciation system that uses the Latin alphabets to phonetically transcribe Hanyu (Han language, the official language) according to 普通话Putonghua (Standard Mandarin) for international use. Approved by the government just 9 years (1958-02-11) after the establisment of the People's Republic of China (1949). In 2000 it was set to law. Since then it has been in use as a teaching tool in primary school. Pinyin is nothing new, and various systems had appeared in China since antiquity, mainly used by officials between regions. It was especially sophisticated during the influx of foreign religions and during contacts with foreign cultures such as those of Japan, Korea, and much later, the Europeans. Today much of written pinyin is written without tone marks, as there can be no replacement of the actual Chinese written word. Its use is mainly to faciltate its transcription using a small set of recognizable alpabets that can be easily incorporated in foreign media.